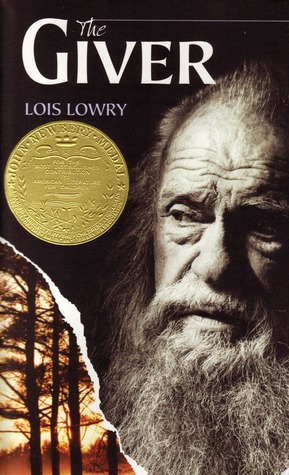

When defining the "classic", one often must apply an arbitrary cutoff date. A book simply cannot be a classic if it hasn't endured a minimally prescribed test of time. My postgrad ongoing classics reading has taken me as far back as 1813's Pride and Prejudice, and, until now, as late as 1989's The Joy Luck Club. I have generally viewed 1990 as a respectable barrier. With The Giver, this barrier has been toppled. Put in perspective as well that the volume of Novels for Students this book appeared in was probably from around 1998, so at the tender age of five this novel was already required reading in schools. While I have kept a mental list of classics I missed because my school was trying to be edgy and different (it was the early 1990's), I can legitimately say I never read The Giver in high school because I had practically graduated by the time it was published.

The Giver has been hailed as one of the first YA dystopias, a now-flourishing genre about hi-tech gladiator-style last-man-standing melees, the moon screwing up the Earth, and people dying from runaway fountain-of-youth treatments. And those are just the ones I've read. The Giver, in a clever move all of its own, present a utopian world so extreme it is actually a horrifying dystopia. In fact, the stunning lack of perception by the characters goes beyond the moral and straight to the physical. I can't say more without wrapping this whole post in spoiler alerts, but Lois Lowry's narrative is confined by what her protagonist can observe. This is why Hollywood didn't pump out a movie before the ink dried on this book. Basically, a scene-for-scene adaption would be totally stupid since Lowry is using the reader's own vision of the world of The Giver, while a movie provides a common visual for all who watch it. Since the movie wasn't universally panned, I suppose they found a way to address this, but not to everyone's satisfaction. I guess I'll just to need to watch (and judge) for myself.

As for my own thoughts on the book, like many, I was confounded by the ending, but unless you are the hero of TNT drama, you probably aren't going to be able to fix an entire broken world. Probably the best feature of the book is the narration itself. We learn as we read just how handicapped Jonas really is because of the utopia/dystopia that has formed him. Undoubtedly the book's intended audience in young adults, so the worldviews are more black and white than equivalent literature for adult readers. If you are under 30, you've probably already read this book already. For the over-30 crowd, enjoy the opportunity to read a young classic without it being force-fed to you.

Wednesday, September 30, 2015

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

Green Shadows (Fleetwood Mac, 2003)

A couple weeks back I foolishly deleted this album from my library (not intentionally) and had to resurrect it from a backup wisely kept on an external hard drive on another computer. Needless to say this collection isn't exactly Rumours, an album you could probably hit was a stone thrown at random into a field of albums. The whole situation was very much on my mind when it was time to pick the next album of the week, and it was a little weird that it should be this one. I even had to double check to confirm it was random.

I'm not sad about this because early Fleetwood Mac is awesome and this was way overdue. Unfortunately, early Mac is really confusing. First, it doesn't sound anything like the radio-friendly stuff of the late 1970's and early 1980's. In fact, with the exception of "Oh Well (Part 1)" getting the occasional live workout, even the band's most devoted fans have likely heard nothing from this era. Second, the control over the catalog from this era was sloppy at best, so much so that an American release (English Rose) was nothing more than an odd mishmash of material from previous and upcoming British albums. Third, no matter how "tormented" the band was at its commercial peak many years later, this was a band the suffered from serious personnel convulsions that would jettison leaders (Green, Spencer, Kirwan, Welch) with a frequency that would have killed any other band. Of the three, point two is what makes this compilation a little hard to follow.

Green Shadows isn't really a "best of" the Peter Green era; it's more of a rarities collection. Most of the songs are either scratchy demo versions, even scratchier live versions (which may predate the first album - there are no helpful liner notes here), and "un-issued" alternate versions of studio tracks. It covers from (probably) just before the first album to 1970's "Green Manalishi" single and Green's departure from the band. For a period of just under three years it shows a lot of change, from blues covers, to blues-inspired originals, to not-even-that-bluesy originals. Although the band was called "Fleetwood Mac", the public secret was that this was Green's band, named in hopes of landing Fleetwood and McVie for his rhythm section, which he ultimately succeeded in doing. All three, along with slide guitarist Jeremy Spencer, carried serious British blues credentials, though the sound was almost entirely directed by Green and Spencer. Like most of the bands of the British blues boom, they soon started to wander into other musical fields. As Spencer was increasingly marginalized, the band got less bluesy, also fueled by the addition of guitarist Danny Kirwan, who ultimately replaced Green completely. Spencer held on a little longer, but was whisked away into a cult and severed his relationship with the band. Bob Weston and Bob Welch joined later than the scope of this compilation, but they are also a part of the extensive "prehistory" of Fleetwood Mac.

I could go on, but, as you might have noticed, I'm running a little behind schedule here!

Thursday, September 10, 2015

The Federalist Papers (Alexander Hamilton, James Madison & John Jay, 1788)

Without fail, I always manage to find a book each year that totally throws me off my game. Up until July I was well on my way to crushing a nice book-a-week pace, but then history intervened. Well, history and a particularly addictive new app on my phone. Compound this little matter with the fact I'm super busy at work and you can plainly see the blog is suffering. I've come to think of this project as doubling as an exercise in journaling, which, in its own way, keeps me stable, so in spite of Work Mountain on my shoulders, I'm going to try to add a little something each day here and get caught up.

Without fail, I always manage to find a book each year that totally throws me off my game. Up until July I was well on my way to crushing a nice book-a-week pace, but then history intervened. Well, history and a particularly addictive new app on my phone. Compound this little matter with the fact I'm super busy at work and you can plainly see the blog is suffering. I've come to think of this project as doubling as an exercise in journaling, which, in its own way, keeps me stable, so in spite of Work Mountain on my shoulders, I'm going to try to add a little something each day here and get caught up.Anyway, the Federalist Papers was on my to-read list for a long time, almost as long as it took me to read all 85 articles, complete with the introduction, supplements, and footnotes. While it certainly isn't an easy read, and parts just patently don't hold up anymore, it's something that every American should endeavor to read at least once in their lifetime.

The idea of reading the Federalist came back around 2008 when I read Ron Chernow's door-stopper of a tome on Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton wrote the majority of the articles, though Madison wrote the most influential ones. Jay wrote about five of them, mostly at the very beginning. For what it's worth, the pseudonym "Publius" is essentially Hamilton's creation. As time went on, it was clear that Hamilton stayed most faithful to the philosophy of the work, while Madison, under the sway of Thomas Jefferson, would stray. Jay remained a Federalist, but would be better known as the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and a governor of New York, than a major political thinker.

The Federalist is not a blueprint for government, but a commentary (and an opinionated one at that) on the hottest document of the day, the proposed Constitution for the United States. Needless to say, the Constitution went far beyond the original aims of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, not merely "revising" the Article of Confederation, but effectively tossing them out and replacing them with a model of a strong central and national government paralleling that of the state governments. With the American Revolution still fresh on everyone's minds, the notion of creating a strong national government structure was greeting with ample skepticism and much arm-twisting and cajoling was going to be needed to get enough states to ratify the document. One particularly hot battleground was New York, and therefore the perfect place to publish a series of articles defending the new Constitution and debunking the critics.

The articles aren't perfect. One particularly telling section is a dismissal of the need for a Bill of Rights, something that obviously didn't go Publius's way. Also, over time the idea of the Senate being created from appointments by state legislatures fell into disfavor and was ultimately replaced by direct elections under the 17th Amendment. However, in the Federalist, Publius really goes to bat defending the old model, as a way of keeping that body distinct from the House of Representatives. Also the language is slightly archaic, so it's easy to miss some of the points being made if one reads them too quickly. However, that is not a fault of the authors, but more of a caution to prospective readers.

To repeat, if you have the time (allow a month) and an interest in American government, consider taking the plunge and reading the Federalist. Short on time? As an American citizen (or American enthusiast), take it upon yourself to at least read the supplements: The Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. You'll be a better person for it, and you will realize how little our current politicians understand American government in this era. Conversely, if you have another month to burn, do what I plan to do in the future: read the so-called Antifederalist Papers, a collection of writings by those opposed to the Constitution. Although branded the "losers" in the history books, a number of their ideas would survive ratification, leading to both good and bad things, like the Bill of Rights and the Civil War respectively.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)